A (F1) Star is Born (1991 - 3).

"Everyone thinks that Schumacher is going to blow me into the weeds. That basically,

I will be history. But that's not going to be the case. He's the guy who has got the

reputation and he is going to beat the world.... He thinks he is going to blow me off.

That's quite apparent from his manner and that's just fine by me. We'll see. Let's

count them up at the end of the year."

- Michael's 1992 team mate Martin Brundle assessing his prospects at the beginning of

the season.

"German male drivers are the most aggressive in Europe and this feeling of power behind

a wheel, this desire to dominate in a fast car, is stronger than elsewhere. It's not new.

It goes far back in history and has been developed over many generations, this inherited

internalised frustration of the German. Jung would have called it a basic national

characteristic."

- Carmen Lakashus, leading Frankfurt psychologist.

Michael Schumacher's entry into Formula One opened up a whole new world to him that his earlier racing career, impressive though it was, could not have entirely prepared him for. Formula Three (or any other motoring sport for that matter) is about as similar to F1 as travelling economy class is to a flight on Concorde. F1 is the ultimate postmodern arena: this most glamorous and decadent of all motor sports transforms little known drivers into world wide celebrities under the constant glare of the media. Everything is subordinated to the spectacle: safety measures are bemoaned by the masses for spoiling the excitement of a race, hence the safety car used to control the speed of the drivers in bad weather is used as little as possible, sometimes with fatal consequences. The true fans of the sport are kept well away behind huge iron gates, but any fairly decent looking celebrity who expresses the slightest interest is welcomed in with open arms. And as for women...as far as the organisers are concerned, F1, like James Bond movies, is a male heterosexual fantasy where the men control everything that matters and the women ("grid girls") are beautiful and vapid and dress in Lycra catsuits. They want to keep it that way. "There is something aspirational about Formula One. Fast cars, wealth, glamour, sex, danger. They are a potent mixture. Other sports contain elements of these, but none contains them all" (1).

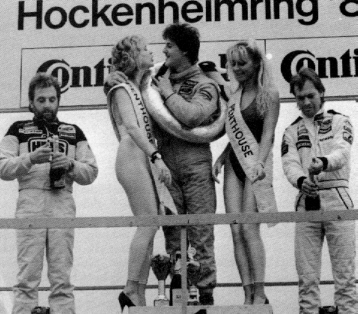

Growing up in a sexist environment: by F1 girls had moved from the podium into the paddock and from swimsuits into catsuits.

Formula One, then, strikingly illustrates the well-known links between "cars and sex". Freud believed that the penis was symbolised in dreams by anything that was long and suggested penetration, and whilst he did not specifically refer to cars he did mention airships. Most post Freudians have realised the importance of the car as a phallic symbol - British psychoanalyst Peter Fuller, quoted in F1 Racing magazine, concluded that a racing car signifies "the externalisation of the phallic fantasies of those who participate, and those who watch" (2). This phallocentric connection is now recognised universally, and is capitalised on by the media in car adverts (my favourite - the Peugeot 306 commercial in which the female character becomes sexually aroused whilst watching her husband wash the car. Their small son promptly appears to distract their attention from sex). This has been noted by racing drivers as well, as Ben Elton testifies:

"The great racer Stirling Moss claimed that there are two things a man will never admit

he does badly, drive and make love, which is a strange irony, because most people

are not particularly good at either. None the less Stirling was probably right, it is

difficult to imagine a bloke in a pub saying 'I nearly caused an accident last night

then went home and couldn't get it up'"

Victory on the racetrack can therefore be considered to have sexual connotations. This sexual motive is important to Michael, as we shall see. He proved a natural in Formula One, as he had in every other formula he had competed in, qualifying seventh in his debut race at Spa, Belgium, despite never having raced there before. A year later he would take his first win there, becoming only the third German driver (after Wolfgang von Trips and Jochen Mass) to ever win a Grand Prix and the fourth youngest-ever race winner. However, Michael also courted the controversy that has dogged his whole F1 career from its very start, as a dispute with Jordan over his contract led to him joining the Benetton team after only one race. The political wrangling that followed his Spa debut was a complicated affair in which Michael himself took little active part, although his reputation still suffered as a result. The "trouble with Schumacher" was never forgotten, especially by Eddie who could only watch in frustration as the young man began winning races. The Jordan team would have to wait another seven years for their first victory.

The sweet faced twenty-two year old brought a breath of fresh air to the sport with his unabashed displays of joy (and tears, in those early victories) on the podium. He also made quite an impression on his early teammates - Brazilian triple World Champion Nelson Piquet, Britisher Martin Brundle, and the Italian Riccardo Patrese. The three were all very experienced drivers and were all in turn outqualified and outpaced by the young charger. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, they found this hard to accept: only Brundle took it with grace and thus maintained a good relationship with Michael. Even the great Brazilian driver Ayrton Senna (pictured right) was forced to take note as the young German began to challenge him on the race track. Senna disliked this new rival, with whom he had many memorable on-track battles and collisions (some of which were Michael's fault, some Ayrton's) and attacked him both verbally and physically. He once grabbed Michael by the throat after an incident during a test session at Hockenheim, Germany, in which the Brazilian felt that the German had deliberately brake tested him. Senna used the same oppressing techniques on Michael as elder siblings often use on younger ones - infantilising him into the Imaginary (Senna once said of Michael that "he's only a stupid boy" (4)), whilst stressing his own superiority and position in the Symbolic - "I have won almost 40 Grands Prix....and he only one" (5).

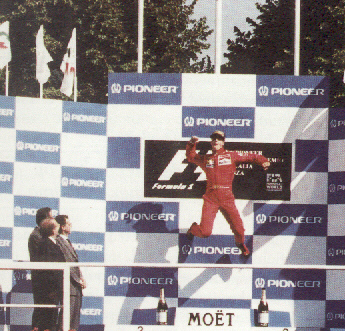

Michael, however, refused to be intimidated by this, and was confident from the beginning that he could beat even the man then considered to be the world's best Grand Prix driver. He stood up to Senna in their frequent confrontations, laying the blame on him for "dangerous driving" when they battled for track position in Senna's home race in 1992. Michael clearly gets sexually aroused by his victories over the other drivers - he jumps on the podium (pictured below) in an attempt to release this sexual tension. He won a more literal sexual victory when he got his revenge on Heinz-Harald Frentzen for beating him in Formula Three by doubly castrating him in F1, surpassing him on the track and stealing his girlfriend Corinna Betsch.

1)

See Hotten, Russell (1998) Formula 1: The Business of Winning, Orion Business, London, p.xiv.2) See Donaldson, Gerald, "Formula 1 drivers are sexually disturbed little boys, crazed speed addicts with flat-spotted brains. They are lunatics with a death wish. Have they been...DRIVEN MAD?" in F1 Racing, October 1997. It is hard to tell whether we should take seriously the same article's claim that "[Melanie Klein] psychoanalysed several F1 drivers and found that they were disturbed little boys who associated the racetracks with their mothers' bodies and the cars with their fathers' sex organs. According to Klein, cornering a racing car represents coitus with the mother, and the threat of an accident is symbolic of castration from dangerous paternal phallic symbols". Given that Klein was primary a child psychologist, this assertion seems somewhat unlikely, though these are similar conclusions to those she reached from watching children play with toy cars.

3) See Elton, Ben (1991) Gridlock, Sphere Books Ltd, London, pp.207-8.

4) See Collings, Timothy (1995) Schumacher: The Life of the New Formula One Champion (revised edition), Bloomsbury, London, p.124.

5) See Collings, Timothy (1995) p.138.

ã Robin Tamblyn, 2000.

All rights reserved.