Big Breaks (1999).

"We're still at the stage in the season where anything can happen. All I need is for

Mika and Michael to have some bad luck and I'm right in there. In the normal run of

things I can't beat Michael so we'll have to wait and see how it pans out."

- Michael's team mate Eddie Irvine's response upon being asked whether he had title

aspirations in 1999, quoted in F1 Racing magazine, August 1999.

"The situation between us is the same as it was before the first race and I would be

very surprised if it had changed. I have the upper hand so far and I haven't seen a sign

that I do not have it any more....I don't see myself as being that unlucky."

- Michael dismissing Eddie's chances of winning the championship after his

maiden Grand Prix victory in Australia.

"He's a star, an anti-hero, and a villain. He's the best driver in the world, and

your worst enemy on the track. He's intimidating and he's awesome. And F1 as a show

and a sport is much the better for having him."

- Autosport's Andrew Benson reflecting on Michael's surprise comeback at the Malaysian GP.

1999 proved to be a very good year for one Schumacher, and a very bad year for the other one. At start of the season, the gloomy predictions that were being made by everyone (including Ralf!) about the poor reliability of the new Williams car were not fulfilled. Despite the lack of power of the Williams Supertec engine, Ralf had his best-ever start to the Formula One season with a third place in the first race in Australia and a fourth place in the second race in Brazil. Ralf thus conclusively beat his new team mate, Champ Car star Alex Zanardi, who did not manage to score a single point all season. Things were very different in the Ferrari camp. Michael failed to get any points in Australia after stalling on the grid (the race was won by his team mate and long term underdog Eddie Irvine), and began to openly criticise Ferrari for the first time since he joined them in 1996 for not providing him with a competitive enough car. Ralf went into the third race leading his brother in the championship table for the first time, with seven points to Michael's six.

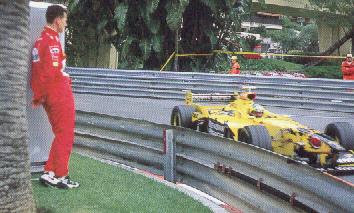

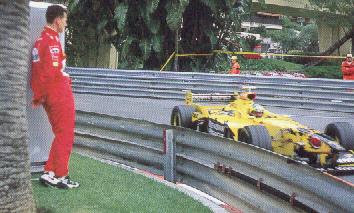

Michael fought back to win a masterly victory at Imola five years after Ayrton Senna's death there, whilst Ralf spun out, along with most of the rest of the field, and a similar thing happened in Monaco two weeks later. However, after a mediocre race at Spain, where he finished nineteen seconds behind Hakkinen, things went rapidly downhill for the man who claims to make only one mistake all season. In Canada he lost control of the car whilst leading the race on lap 30 and slammed sharply into the wall, letting Hakkinen grab victory and take the championship lead. The following Grand Prix in France provided a sharp contrast to the 1997 race in which he gifted his younger sibling a point, as now he found one taken away as he was unable to prevent Ralf from overtaking him (to claim fourth place) in the closing stages of the race. "This time we were just better", gloated the little brother (1). Worse still, at Silverstone Michael locked up his brakes on the first lap and spun off the track to smash into the tyre wall at over 60 mph (see picture above left), breaking his right leg in the process. The race was restarted and Ralf, who appeared concerned but not devastated once assured that his brother's injuries were not life threatening, drove a masterly race to grab third place on the podium. His mistake at the British Grand Prix was without doubt the biggest error Michael has ever made in his twenty-six year racing career (2); it cost him the World Championship before the real fighting had begun and thus left the man contracted as his number two to wage his own Championship battle. However, had it happened before the safety measures introduced after the deaths of Senna and Roland Ratzenberger in San Marino it would probably have cost him his life as well. This accident is bound to affect Michael psychologically as it was the first time he had ever been hurt badly enough to miss a Formula One race.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, Ralf proved to perform even better as he was no longer directly in his brother's oppressive shadow for the first time in his F1 career. Although a clumsy attempt to prevent Pedro Diniz's Sauber from overtaking put him out of the Austrian race after only a few laps, at his home Grand Prix a week later Ralf drove a magnificent race once more. He qualified in only eleventh position but worked his way up to eventually finish fourth behind the much more powerful Ferraris and the Jordan of Heinz-Harald Frentzen. Murray Walker, dramatically revising his opinions of Ralf from 1997, named him the "man of the year" early in the season and found this well justified later. True to his word, Murray eventually placed Ralf at number one in a list of the top ten drivers of the year, whilst Michael was only classified fifth! (see Appendix). At last Ralf appears to be moving away from his brother's pervasive image: the Sunday Times noted in April 1999 that: "[Ralf] has finally established his own identity: no more will he constantly be referred to as 'Michael Schumacher's brother'"(3). His good performances in 1999 soon attracted the attention of the new Stewart-Ford superteam, who offered him £6 million to move to their camp at the end of the season. Ralf chose to stay with Williams, claiming that he was willing to wait for the new BMW engine that the team was developing for the new millennium (4). Ralf continued to wring the best possible performances from the feeble Supertec in 1999 - he finished second at the Italian Grand Prix and came tantalisingly close to winning in front of an enthusiastic German crowd at the wet weather Nurburgring two weeks after that.

If there had been any doubt remaining among the F1 fraternity of Ralf's now outstanding talent behind the wheel of a Formula One car, this race surely must have dispelled it. Ralf qualified in fourth position and kept up the pace behind pole sitter Frentzen and the McLarens. An assertive move early on put him in front of David Coulthard. Though he found himself behind the Scot again after his first pit stop, after Hakkinen made an unnecessary stop, Frentzen had an electrical fault and Coulthard spun out, Ralf found himself leading the race. The team called him into the pits for wet tyres as the rain grew heavier, but Ralf believed that he could keep going on slicks. He was right. Ralf looked to be in a commanding position until a late puncture on lap 50 robbed him of his rightful victory - as ITV commentator Martin Brundle said, "If there was a man who deserved to win this race, it was Ralf Schumacher" (5). Ralf managed to keep his concentration after a pit stop for new tyres and eventually finished fourth. This shows that he has matured as a driver even since last year when he would probably have abandoned the race in his disappointment at losing the lead. And what a contrast to the Nurburgring race two years previously, where Ralf took himself and three other drivers (6) out of the race early on. It is unlikely that Michael could have done better under the circumstances. Ralf's fourth place here put him in front of his brother in the championship table again and probably helped to influence Frank Williams to offer him a lucrative new contact worth £9.7 million per annum. Only Villeneuve, Hakkinen and Michael, all world champions, are believed to earn more. For Frank to be willing to pay this much for a driver who has not even won a race yet is surely a measure of the faith he must have in Ralf, especially when considering the fact that he fired Damon Hill for asking for a pay rise.

Ralf, then, is now a fully mature Formula One driver with a pay packet to match. He seems to have grown as a person too - this year he has avoided the childish attacks on fellow drivers that were a regular feature of his behaviour both on and off the track during the 1997 and 1998 seasons. As a result, his popularity in the paddock has risen dramatically - no one has a bad word to say about him these days (7). In sum, then, things could hardly get better for Ralf. For Michael, however, it was a very different picture. Ferrari did not appear to be missing Michael's input as much as had been expected - they scored a 1-2 finish at the German Grand Prix with Irvine and Michael's stand in Mika Salo. Irvine also won in Austria and came second in Britain and Hungary. The McLarens made so many mistakes in the second half of the season that Michael, watching from his home in Switzerland, must have been especially frustrated to think that if he had not broken his leg he would easily have won the drivers' title. Instead, he was forced to accept that the team he had worked so hard to build up to World Championship standard appeared to no longer need him, and that the sport in which he had held centre stage for five years was still enthralling public viewing even in his absence. Inevitably, perhaps, the self centred German could not be happy for Ferrari. He was unable to resist attacking Irvine, the man who had been his faithful number two for so long and who of all people most deserved his support. Michael told reporters just prior to the European Grand Prix at the Nurburgring that Eddie had "no chance" of winning the championship unless Mika threw it away (8).

Despite such vilification of his team mate's ability, Michael eventually decided to return for the final two races of the season to help Irvine's championship battle, defying the wishes of both his wife Corinna and his long time manager Willi Weber (a man who, like Michael's ex-press officer Heiner Buchinger, bears more than a passing resemblance to Rolf Schumacher - could it be that Michael is searching for substitutes for his faithless father?). Weber warned Michael that if he was injured again before the pins in his leg were removed, it could put him out of racing altogether, but, stubborn as always, Michael, spurred on perhaps by the knowledge that Ralf was now ahead of him in the championship table, refused to listen. Weber's fears, fortunately, proved to be unfounded. Michael left his rivals open mouthed with amazement at his comeback in Malaysia when he set pole position by a full second.

"The only small negative side is that there's one big competitor back and one guy to try to take our points away, but that's the way it is", mused Ralf to ITV Sport just before the race began (9). Did Michael's return cause Ralf to perform badly? It certainly appeared so - Ralf qualified in only eighth position and spun off the track and into a gravel trap on the seventh lap. He was once again castrated by his brother's stunning drive as Michael - who had been out of action for three months and had not driven at full race distance since June - gave one of the best performances of his career. Michael led for the first and last sections of the race, keeping Hakkinen and the others at bay, then, confounding those who said he would refuse to obey team orders, conceded the lead to Irvine. Whilst it must have been frustrating to give up the win, Michael was at least able to console himself with the knowledge that he had snatched back his fifth place in the championship table from Ralf (10). The media were forced to dramatically revise their opinions of Michael in the light of his selfless actions in Malaysia. The Daily Mail gave the most striking appraisal: "Schumacher has been branded an arrogant, greedy, stone-hearted and totally self-centred man. But here, in a strategically compelling grand prix, the 31 [sic] year old German revealed the depth of his devotion to Ferrari and his commitment to team mate Irvine's quest" (11). Michael thus appeared to have once again partially redeemed himself at the end of the season, however (as was also the case the previous year) he spoiled the effect by an unjustified attack on a fellow driver after the Japanese Grand Prix (see below).

The return of his castrating big brother was clearly bothering Ralf in Japan as he spun off during the qualifying session, which had done so often in 1997 and so rarely during Michael's absence in 1999. He eventually posted ninth whilst Michael coolly took pole. Michael was again required to undertake a supporting role to Irvine - oddly, this time his goal was to win the race and thus make sure that Hakkinen could not get more than six points, meaning that Irvine would only have to finish fourth to be champion. However, Michael made a poor start, which let Hakkinen grab the lead on the first lap. Considering the way he had streaked ahead of the field two weeks earlier, it seemed strange that Michael could not keep pace with Hakkinen here. Martin Brundle, Michael's 1992 team mate and a man who knows him well, voiced what everyone suspected - he clearly was not trying (12). The rest of the race was pretty much a procession, with Hakkinen leading and Irvine languishing in fourth position behind Hakkinen's team mate Coulthard, under team orders to hold him up. An early second pit stop got Irvine out from behind Coulthard, but it was not enough. Hakkinen eventually won by over five seconds from Michael, with Irvine third and Ralf, benefiting from numerous retirements, finishing fifth. This left Hakkinen with the Driver's Championship, Ferrari with the Constructors Championship (their first since 1983), and Michael with his dream of becoming Ferrari's first World Champion since 1979 still intact.

It appeared that Michael was happy with this conclusion to what had been for him a very bad season, though he showed his old devilry at the press conference after the race with an attack on Coulthard, who had appeared to block Michael as he came up to lap him. Inevitably, the ghost of Spa was raised again: "Actually, I'm not sure whether I should believe Spa wasn't done purposely, the way he behaved today" (13). Considering the criticism from all quarters that Michael received after this previous incident, he is unwise to be trying to bring it back into public consciousness. David retaliated by joining the chorus of voices accusing Michael of not having wanted Irvine to win the championship and by threatening legal action (!) unless he withdrew these remarks. It therefore appears as if the feud between Michael and the man he once claimed to "understand very well" is on again. Like Freud, Michael seems unable to cope without a "hated enemy" in his professional life. Since Damon Hill is finally retiring, it seems perhaps logical for his one time Williams team mate to take over the "nemesis" role to Michael. Ralf, incidentally, is unlikely to approve of this - Coulthard is his favourite driver. For his part, David has always admired Ralf, recently remarking that "in the right equipment he could easily emulate his brother's accomplishments some day" (14).

The 1999 season offers compelling evidence that this will indeed soon be the case. Michael does not want Ralf in the same team as him as "it means one of us has to lose and we wouldn't like that" (15). Clearly Michael is worried that he could eventually be the loser. He has recently stated (in an interview conducted by Damon Hill!) that he would retire in the event of some young charger emerging to steal his "world's best driver" crown - therefore, if Ralf does succeed in his dominancy fight he may well drive his brother off the F1 battlefield for good (16). However, Ralf still has a long way to go - we have to remember that he has not even won a race yet. The best evidence that Ralf can beat Michael on the track is probably his qualifying performance during the 1998 German Grand Prix when he posted fourth to Michael's ninth and thus outshone him on home territory. Another good example is the 1999 French Grand Prix, when he conclusively surpassed Michael in as straight fight for the first time in his F1 career. Ralf showed on the track in France and also in the 1998 Austrian Grand Prix that he does not let Michael past easily just because they are brothers. He clearly wants to win - and is getting better all the time. Michael will fight back as he does not want to be symbolically castrated. He was noticeably subdued in Austria, although he did manage to congratulate Ralf after the race. Michael can perhaps console himself with the thought that Ralf can never take away all of his prestige - he will always be Germany's first World Champion and will probably remain the youngest ever double World Champion (17).

How long will it be before Michael is watching Ralf from the sidelines permanently?

At any rate, the 2000 season looks set to be an intriguing one with Ralf, complete with a powerful new BMW engine, paired with a younger driver for the first time in his Formula One career - Somerset's Jensen Button, at just twenty years old the youngest British F1 driver ever and on a mission to be the youngest ever World Champion too. Michael, meanwhile, has a new team mate for the first time since he joined Ferrari, the promising Brazilian Rubens Barrichello, who has repeatedly declared himself determined not to suffer the fate of all Michael's previous team mates and be forced into a subordinate role.

1)

See Schumacher, Ralf, quoted in Autosport, July 29 1999.2) Whilst the force of the impact was due to the Ferrari's rear brake failure, the accident itself was mostly Michael's fault as he went off the track trying to overtake Irvine - as if he needed to battle with the man who is contracted to play second to him! Clearly another case of the hunter refusing to give up the chase - with dire consequences.

3) See Windsor, Peter "Ralf comes of age", in The Sunday Times, April 4 1999.

4) See Schumacher, Ralf, quoted in Autosport, August 19 1999.

5) See Brundle, Martin, quoted on ITV Sport, September 26 1999.

6) Besides Michael and Giancarlo Fisichella, Ralf also managed to displace the Japanese driver Ukyo Katayama.

7) It should however be noted that Ralf has yet to win over the fans' affections. Thousands stayed away from Hockenheim due to Michael's absence - Ralf is clearly in some ways still a poor man's Michael Schumacher.

8) See Schumacher, Michael, quoted in The Daily Mail, September 25 1999.

9) See Schumacher, Ralf, quoted on ITV Sport, October 17 1999.

10) The World Championship took an unexpected turn when Michael and Irvine were disqualified soon after the race had finished on a minor technicality (the car's sidepods were a centimetre under regulation length). However, they were later reinstated after a tribunal accepted the team's argument that this had not affected the car's performance and that the discrepancy was within normal tolerance levels.

11) See Matts, Ray "He couldn't even be king for a day", in The Daily Mail, October 18 1999.

12) See Brundle, Martin, quoted on ITV Sport, October 31 1999.

13) See Schumacher, Michael, quoted on ITV Sport, October 31 1999.

14) See Coulthard, David, quoted in The Daily Mail on Sunday, December 19 1999.

15) See Schumacher, Michael, quoted in Autosport, January 20 2000.

16) See Schumacher, Michael, quoted in F1 Racing, January 2000.

17) Michael almost became the youngest ever World Champion too: when he won his first drivers' title on the thirteenth of November 1994 he was just 16 days older than Emerson Fittipaldi (born on the twelfth of December 1946) was when he won the World Championship on the eighth of October 1972. Ralf, meanwhile, holds an impressive record of his own: he became the youngest ever driver to stand on the podium with his controversial third place at the 1997 Argentinian Grand Prix.

ã Robin Tamblyn, 2000.

All rights reserved.